Today, let us remember two Australian brothers who paid the ultimate price during the first world war. I discovered their story when researching for my 2016 Anzac Day address. Stories like theirs should never be forgotten.

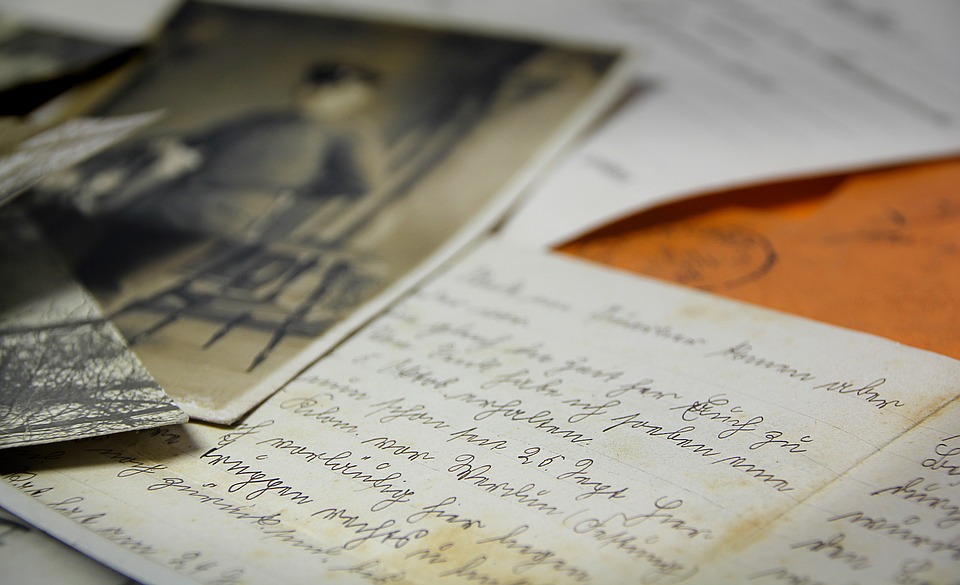

IN 1927 THE AUSTRALIAN WAR MEMORIAL’S DIRECTOR, JOHN TRELOAR, WROTE TO THE REVEREND JOHN GARRARD RAWS, ABOUT WARTIME LETTERS OF HIS TWO SONS. HE ASKED IF THE REVEREND MIGHT CONSIDER DONATING THEM TO THE MEMORIAL. THE REVEREND REPLIED THAT SADLY THE ORIGINAL LETTERS WERE NOT PRESERVED, HOWEVER TYPED COPIES SURVIVED AND COULD BE LOANED. THE COPIES WERE CLEARLY PRECIOUS TO HIM AND HE URGED THEY BE RETURNED AFTER COPYING AS HE SAID, “THEY ARE ALL I HAVE LEFT OF THEM.” HE ALSO ADDED, “I DOUBT IF THEY CONTAIN ANY INFORMATION OF NOTE”. HE COULD NOT HAVE BEEN MORE WRONG.

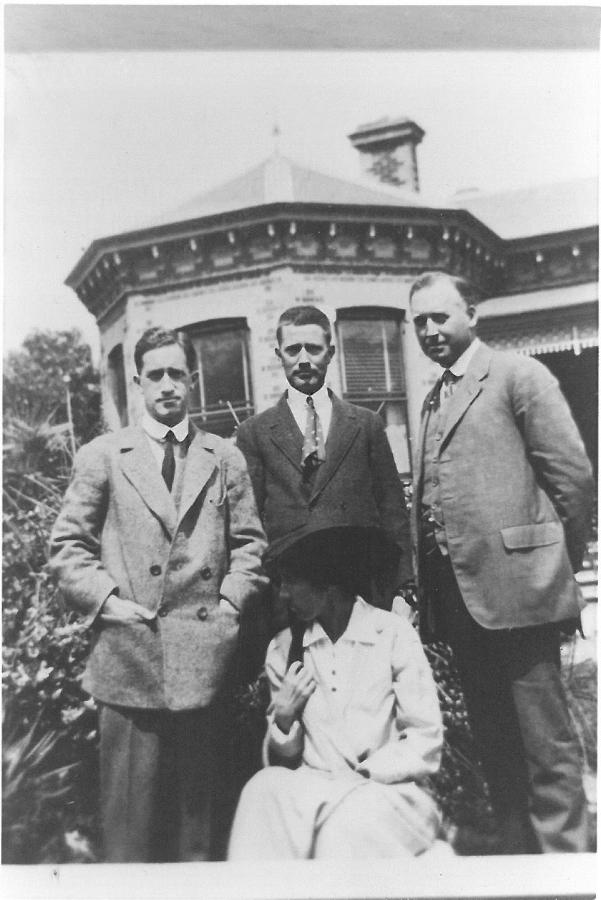

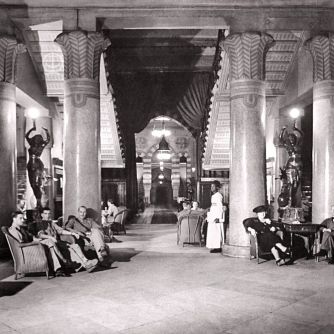

BORN IN MANCHESTER, ENGLAND, IN 1883 AND 1886, JOHN ALEXANDER (ALEC) AND ROBERT GOLDTHORPE (GOLDY) WERE THE YOUNGEST SONS OF REVEREND AND MRS RAWS. THE FAMILY MIGRATED TO AUSTRALIA IN 1895 AND SETTLED IN ADELAIDE BEFORE LATER MOVING TO MELBOURNE. GROWING UP, THE BOYS ATTENDED PRINCE ALFRED COLLEGE AND ALEC SOON BECAME AN OUTSTANDING SPORTSMAN. HE WAS A GIFTED CRICKET BATSMAN AND LATER PLAYED TENNIS AT STATE REPRESENTATIVE LEVEL. EVENTUALLY, HE EMBARKED IN A CAREER IN JOURNALISM AND BY THE TIME WAR BROKE OUT IN 1914, HE WORKED AS A POLITICAL REPORTER FOR THE ARGUS IN MELBOURNE.

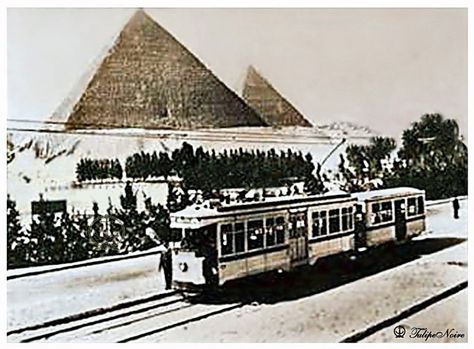

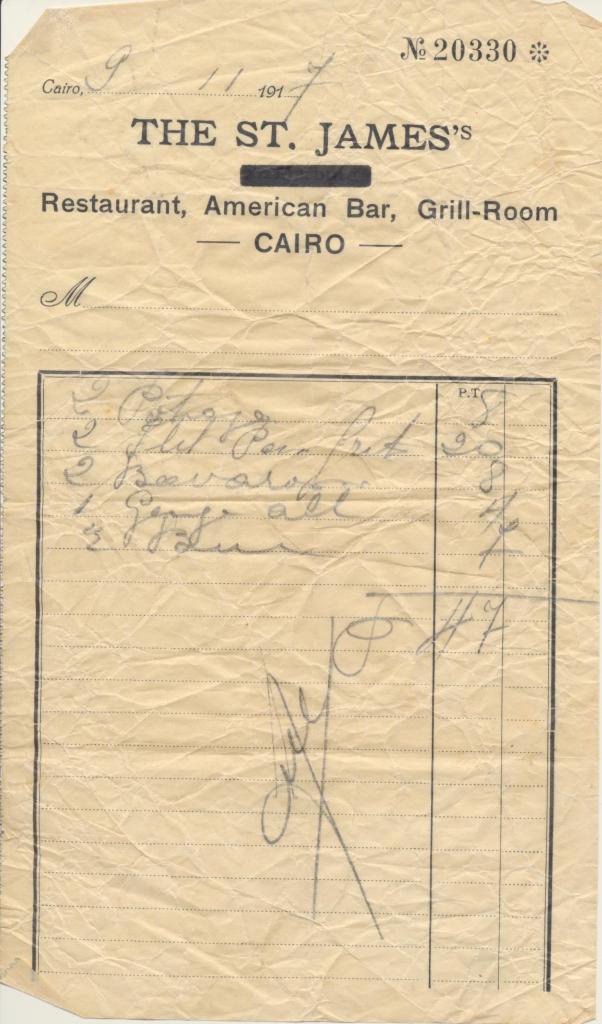

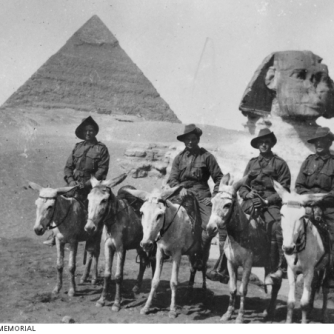

GOLDY, ON THE OTHER HAND, TOOK A TOTALLY DIFFERENT PATH IN LIFE AND BY 1914 WAS WORKING ON A PLANTATION UP IN QUEENSLAND. HE JOINED THE AUSTRALIAN IMPERIAL FORCE IN JANUARY 1915 AND WAS SOON ON HIS WAY TO EGYPT FOR TRAINING. HIS ELDER BROTHER, ALEC, TRIED TO ENLIST AND WAS REJECTED IN THE INITIAL RECRUITMENT, DUE TO HIS SMALL STATURE AND FRAILTY OF HEALTH. HE HAD IN RECENT YEARS EXPERIENCED FAINTING SPELLS AND THE DOCTOR ADVISED HIM TO AVOID EXCESSIVE STRAIN. HOWEVER, HE PERSISTED AND FINALLY IN JULY 1915, TO EVERYONE’S SURPRISE, NOT LEAST HIS OWN, HE WAS ACCEPTED.

IT IS INTERESTING THAT ALEC WAS SO PERSISTENT IN WANTING TO ENLIST, WHEN HE ABSOLUTELY ABHORRED ANY FORM OF VIOLENCE, LET ALONE WAR. SO WHY THEN WAS HE INTENT ON GOING?

IN A LETTER HE WROTE TO HIS FATHER, HE SAID HE WAS NOT GUIDED BY A SENSE OF PATRIOTISM TOWARDS THE BRITISH EMPIRE OR AUSTRALIA. HE WAS DISGUSTED BY HOW MEN IN POWER, GOVERNMENTS AND THE SYSTEM HAD LET THE WORLD FALL INTO SUCH A TERRIBLE BLOODY WAR. AS HE EXPLAINED, HE JOINED UP TO SUPPORT HIS MATES AND BROTHER, ALREADY SERVING OVERSEAS AND TO TAKE A STAND FOR HIS OWN PRINCIPLES AND A BELIEF THAT ONLY AN ALLIED VICTORY WOULD BRING SALVATION TO THE WORLD.

IN THE MEANTIME, GOLDY HAD BEEN AT WAR FOR A YEAR AND LANDED IN GALLIPOLI IN SEPTEMBER 1915 WITH THE 23RD INFANTRY BATTALION AND SAW FIGHTING AT LONE PINE. THEN AS HIS OLDER BROTHER WAS HEADING FOR EGYPT, GOLDY WAS ON HIS WAY TO FRANCE – TO THE WESTERN FRONT.

AS FATE WOULD HAVE IT, IN JULY 1916, ALEC WAS TRANSFERRED TO GOLDY’S BATTALION. BUT GOLDY HAD GONE INTO AN ATTACK THE NIGHT BEFORE ALEC’S ARRIVAL AND WAS DECLARED MISSING. HIS BODY WAS NEVER FOUND.

DESPITE BEING SICK WITH WORRY ABOUT HIS BROTHER, ALEC ALSO HAD TO COPE WITH BEING BRAND NEW TO THE FRONT LINE AT A TIME WHICH SAW PROBABLY THE WORST AND MOST INTENSE PERIOD OF FIGHTING AND CONSTANT SHELLING AUSTRALIANS EVER HAD TO ENDURE. ON 4TH AUGUST 1916, HE WROTE THE FOLLOWING LETTER TO HIS FAMILY AT HOME IN AUSTRALIA.

ONE FEELS ON A BATTLEFIELD SUCH AS THIS THAT ONE CAN NEVER SURVIVE, OR THAT IF THE BODY LIVES THE BRAIN MUST GO FOREVER. FOR THE HORRORS ONE SEES AND THE NEVER-ENDING SHOCK OF THE SHELLS IS MORE THAN CAN BE BORNE. HELL MUST BE A HOME TO IT. THE GALLIPOLI VETERANS HERE SAY THAT THE PENINSULA WAS A HAPPY PICNIC TO THIS PUSH. YOU’VE READ OF VERDUN – THEY SAY THIS KNOCKS IT HOLLOW. MY BATTALION HAS BEEN IN IT FOR EIGHT DAYS, AND ONE-THIRD OF IT IS LEFT – ALL SHATTERED AT THAT. AND THEY’RE STICKING IT STILL, INCOMPARABLE HEROES ALL. WE ARE LOUSY, STINKING, RAGGED, UNSHAVEN AND SLEEPLESS. EVEN WHEN WE’RE BACK A BIT WE CAN’T SLEEP FOR OUR OWN GUNS. I HAVE ONE PUTTEE, A DEAD MAN’S HELMET, ANOTHER DEAD MAN’S GAS PROTECTOR, A DEAD MAN’S BAYONET. MY TUNIC IS ROTTEN WITH OTHER MEN’S BLOOD. IT IS HORRIBLE, BUT WHY SHOULD YOU PEOPLE AT HOME NOT KNOW? SEVERAL OF MY FRIENDS ARE RAVING MAD. I MET THREE OFFICERS OUT IN NO MAN’S LAND THE OTHER NIGHT, ALL RAMBLING AND MAD. POOR DEVILS!

THEN ON 19TH AUGUST HE WROTE:

BEFORE GOING INTO THIS NEXT AFFAIR, AT THE SAME DREADFUL SPOT, I WANT TO TELL YOU, SO THAT IT MAY BE ON RECORD, THAT I HONESTLY BELIEVE GOLDY AND MANY OTHER OFFICERS WERE MURDERED ON THE NIGHT YOU KNOW OF (28-29 JULY), THROUGH THE INCOMPETENCE, CALLOUSNESS, AND PERSONAL VANITY OF THOSE HIGH IN AUTHORITY. I REALISE THE SERIOUSNESS OF WHAT I SAY, BUT I AM SO BITTER, AND THE FACTS ARE SO PALPABLE, THAT IT MUST BE SAID. PLEASE BE VERY DISCREET WITH THIS LETTER – UNLESS I SHOULD GO UNDER.

ON 22ND AUGUST, ALEC RAWS WAS KILLED IN ACTION.

BOTH BROTHERS LIE IN UNKNOWN GRAVES ON THE BATTLEFIELDS OF POZIERES IN FRANCE.

THE LETTERS OF ALEC RAWS WERE THE MOST DETAILED ACCOUNT THE WAR MEMORIAL HAD ENCOUNTERED OF THE WESTERN FRONT. CHARLES BEAN, WAS ACTUALLY ADVISED AGAINST MAKING THEM PUBLIC, HOWEVER, HE CHOSE TO IGNORE THAT ADVICE.

LEST WE FORGET.